Arlene Spicy Cider-Soused Pig’s Trotters

Bar food from rural central Arlen

- Background

- Recipe

This dish’s slangy mid-Arlene dialect name, Khet-mana’ten, translates straightforwardly as “Hot-‘n’-Sweet Feet.” It’s just one of many treatments of pig’s feet (aka “trotters”) extant across the Kingdoms—most of them exhibiting strong regional tendencies, as this one does.

During the events of The Door Into Sunset, the on-the-run would-be King Freelorn comes across this dish in a cookshop in Elefrua—the little town in the Arlene midlands where he was fostered out in childhood—just about at the northern edge of the latitude where apples grow well, and where cider is therefore usually readily available. (N.B. that in all the Four Realms’ languages, the words we’re translating as “cider*” always mean the alcoholic kind. Apple juice is routinely called by names that translate as, well, “apple juice.”)

…The food arrived, and Lorn’s stomach did a fair imitation of the roar of a young lion. “Too long since breakfast,” Lalen said to him, amused, and drank her wine as Lorn reached for the first of the pig trotters. They had been boiled with sage and bay, then soused in cider, from the divine smell of them, and afterwards burnt brown under a hot iron, until the skin had gone crisp.

Freelorn pulled the first trotter apart as delicately as he could, but there was really no way to eat this food delicately, especially considering how it smelled, and the presence of many small bones to be gnawed clean of succulent, herb-scented, beautifully greasy meat.

The word translated in the text as “soused” (Arl. menlikhérou) has more to do with an implied intensity of flavor and unusually-generous use of available ingredients than with the actual method. In this case, it refers to a second stage of cooking after the trotters have already gone through the normal procedure of being long-simmered to near-complete tenderness. (In places where there’s enough cider to spare, this first cooking can take place in half-and-half water and cider, or straight cider alone.)

In the second stage, the pig’s feet then spend another hour or so simmering in more aggressively-spiced cider, to pick up its flavor. The spicing for this routinely involves more “sweet-friendly” spices like cinnamon, summerbark, or the milder berry-peppers (for which, in our version, cubeb and Sichuan peppers stand in). Some places—usually well south of the Arlene midlands—might drop freshly oven-roasted apples into this mixture too, if the season is right.

The third and final stage of this dish calls for the reduction of the cider to a sauce thick enough to coat a spoon, with butter beaten into it to finish. While this is going on, the trotters are brushed with melted butter or lard before (in a Middle Kingdoms kitchen) having a salamander passed over them to crisp up the skins. Since not all that many of us are likely to have either the older version of a salamander or one of the newer ones in our kitchens, our take on the recipe calls for the cooked trotters to be brushed with butter and colored/crisped up under an oven’s grill/broiler. They’re then plated up with a trickle of the cider sauce over, and the rest in a jug alongside (or a bowl for dipping, if the diner prefers).

How to deal with the bones when the cooking’s done and the eating’s begun is always an issue with trotters. The text indicates that Lorn was served full/intact trotters, which makes sense in terms of where he was; a cookshop in a little country town wouldn’t waste time on such fussy niceties as deboning the trotters pre-service. City cookshops further north, though, who might serve the dish (or similar ones) as an evocative rural specialty, will do the initial simmering with only very basic seasonings—usually just pepper, bay and onion. Then they’ll either debone the trotters and shred their meat for further cooking and saucing on demand, or coarsely chop the meat and put it down in an aspic based on the plentiful gelatine released from the pigs’ feet during cooking.

The ingredients list and method for preparing the dish are in the “Recipe” tab.

*The Arlene and North Arlene word is elieun [Darthene eilaen, Steldene eulien]. Ladhain has several words for differing strengths and styles of cider, though none for apple distillates).

The first stage of the recipe involves cooking the trotters more or less completely. But first we need to deal with a level of basic prep that butchers in non-European regions might not know needs to occur for best results.

In the Middle Kingdoms, for curing and keeping meat, salt is the chief resource. It’s readily and plentifully available in almost all the populated areas of the Four Realms—either through local resources (like the great salt caves west of Prydon and south of Darthis in the foothills of the Highpeaks) or via routine trade with other regions. (Specialty “flavored” salts are also traded, as well as sea salt: the need for iodine in the diet is well understood.)

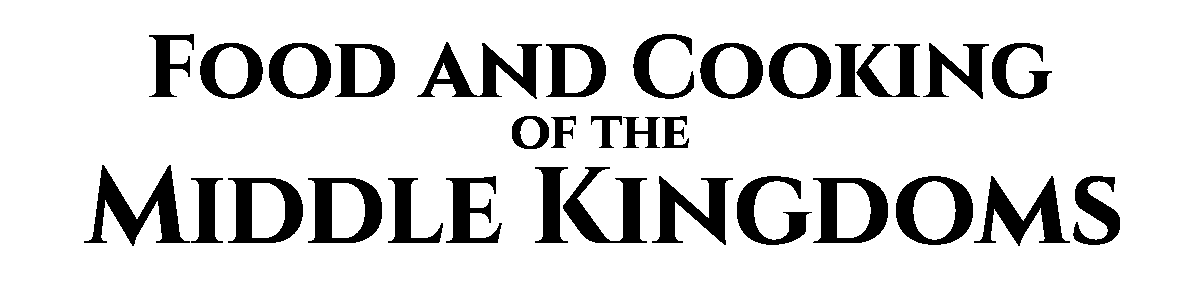

The basic treatment for almost all cuts of pork therefore tends to involve brine-curing, and these trotters are no exception. Best practice maintains that after being scraped and scrubbed by the butcher (and rescraped after any bristles have been singed off), the trotters should be put down in a basic brine for at least 24-48 hours. This tenderizes and flavors the meat. (In our case, we’re fortunate that Irish butchers do this routinely, as pigs’ feet have a very old fandom here. These are the ones we used from Andarl Farm in County Galway. Thanks, folks!)

Once this has been done, the cooking can begin. The ingredients for the first stage:

- 4 brined/salted pig’s trotters cleaned/trimmed by your butcher

- 1 onion, quartered

- At least 4 garlic cloves, peeled and halved, and more if you like (because, as we say around here, “Nobody ever died of passive garlic”)

- A small bundle of fresh sage, or 0.5 teaspoon of dried sage

- 2 bay leaves

- A small bundle of fresh parsley

- 6-12 black peppercorns, depending on how peppery you like things

- 2 small bird’s-eye chilies

- (Optional but recommended: 4-6 Sichuan or cubeb peppercorns)

- (Optional: 2-4 buds of long pepper, Piper longum)

Add the vegetables, herbs and spices to a large pot and fill with cold water.

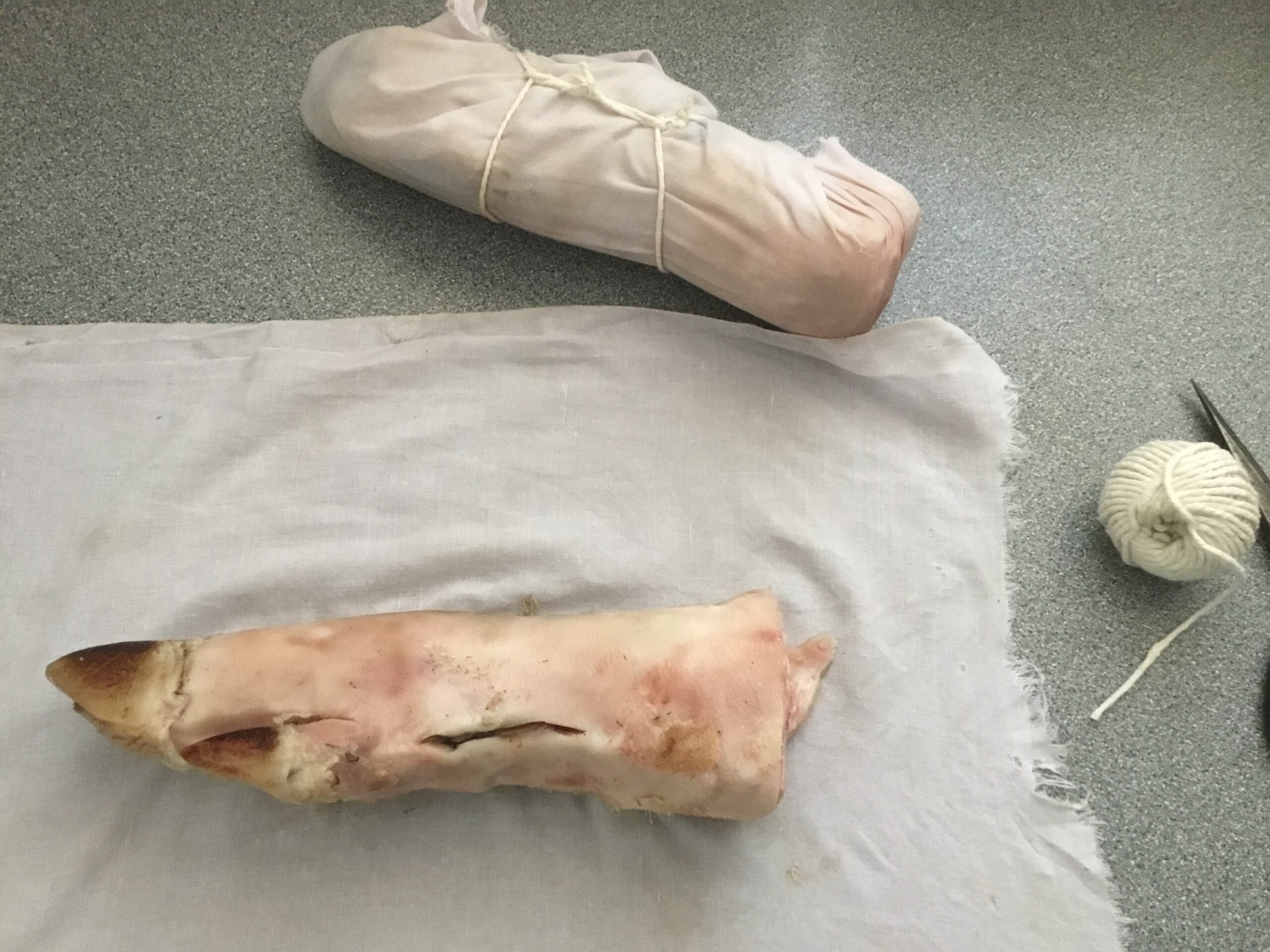

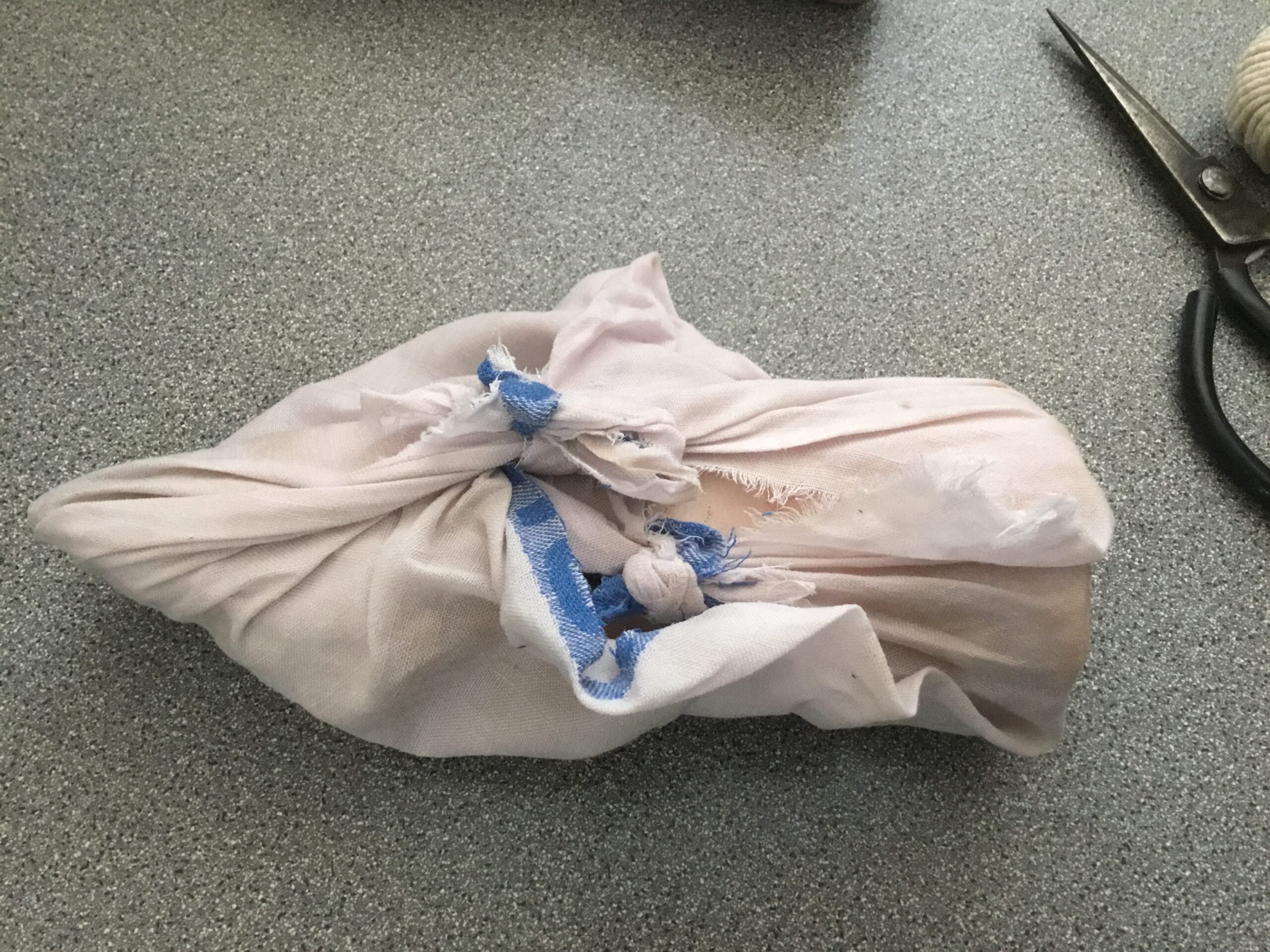

To prepare the trotters themselves (assuming that you or your butcher have already singed, scraped and brined them): rinse in cold water and dry. Then wrap each one in cheesecloth (or a piece of an old cotton or linen dishtowel, if you’ve got one that’s ready to be sacrificed to the rag bag) and tie up well with twine. This will foil the trotters’ otherwise near-unavoidable tendency to fall to pieces during the cooking process. (When properly cooked, they’ll still do their very best to fall to bits afterwards… and careful handling is the only way to defeat these attempts, so be warned.)

Place the wrapped trotters in the pot with the vegetables and other ingredients and bring to a boil. Then immediately reduce to a simmer, cover the pot, and cook for 3.5 to 4 hours.

At the 3.5 hour point it’s wise to investigate whether the trotters are completely cooked yet (as trotters that have been in brine longer than expected can take less time to cook). Fish one out with a fork through its tying twine, allow it to drain briefly in a bowl or in the sink, and then cut the twine and carefully unwrap the cloth bandaging. Test for doneness by (with forks, or your hands if the heat’s not too bad for you to bear) attempting to pull the foot apart. If it’s done enough to be going on with, it should come apart without the application of too much brute force. …If it comes apart very easily, you’re done with this stage of the cooking: get them off the heat. (Do not, however, waste your time being concerned about overcooking these. It’s surprisingly hard to ruin pork that way.) If the trotter resists you to the point where you think it’s something you’d have trouble eating, rewrap it, retie it, put it back in the pot and give everything another half hour. Four hours should really be enough time to see everything well enough cooked to proceed.

At the end of the cooking time, remove the trotters to a large bowl and allow them to drain until cool enough to handle. Have ready a stovetop-friendly casserole big enough to hold them all. (The size of the casserole matters a bit here, as during this second stage of cooking—when the trotters will be unwrapped and are going to get increasingly fragile—you don’t want them to have too much room to move around during the simmering and lose their structural integrity. If they’re packed in moderately tightly, that’s good.)

To this casserole add:

- 6 more black peppercorns

- 1 more birdseye chilli

- (Optional: A few more Sichuan peppercorns [if you have them])

Carefully unwrap the trotters and lay them in this casserole on their sides. Pour over them:

- At least 1 quart / 1 liter of a good alcoholic cider, preferably a dry one: in any case, enough to cover the trotters. You might need two quarts. And having a third liter handy is a good idea, in case you need it to top up the in-pot cider during cooking. (And who knows, the cook might want some. Because frequent quality-assurance testing is so important…)

- (You could probably also add a shot of a local applejack at this point if you liked. It’s entirely optional, but would certainly be very nice.)

Bring the contents of the casserole up to the simmer and cover. (No need to come up all the way to the boil, at this point.) The simmer should be the just-ticking-over, a-little-motion-on-top type intimated by the French verb mijoter.

When the hour’s simmering is over, remove the pot from the heat and assemble whatever utensil or rack you intend to use to grill/broil the trotters. Very carefully remove them from the cider and arrange them in the pan or on the rack. (We used a rack over a nonstick pizza pan.)

Arrange your oven rack or broiler setup in whatever way will put the trotters about an inch under the heat source.

Meanwhile, increase the heat under the cider to a boil. Boil hard until the cider’s volume has sufficiently reduced for the resulting sauce to coat the back of a spoon. Remove from the heat and give it a few minutes to calm down. Use a skimmer or slotted spoon to remove any whole herbs/spices remaining. Then add two or three 2cm/1-inch cubes of cold butter, one at a time, beating with a whisk until the sauce thickens. (Note for reference purposes that when left to cool, the butter will rise to the top of this sauce, and the clear-ish substrate will jell quite firm. This is useful for further preparations, such as the aspic-based one mentioned above.)

Now is the time for the trotters to go under the grill. Melt some butter in a pan or in the microwave and use it to brush the top side of the trotters. Then put them under the broiler and give them about 2-3 minutes beneath it, to crisp up a little and color. (Don’t expect them to crisp up to anything like the crunchiness of, say, roast pork crackling. After what they’ve just been through in terms of boiling, it’s not going to happen. But they will go a bit crisper.) Watch them carefully during this process, as they can go from beautifully browned to seriously unattractively scorched in a matter of seconds. Do not take seriously any sudden popping noises you hear (the skins do that…) unless something is showing signs of actively catching fire.

Remove the rack-or-whatever, allow things to cool down a little bit, carefully turn the trotters over, brush this side of them with butter, and put them back under the grill until they’re colored as you like them.

Then remove them, set aside, and plate up. Bowls actually work better for this, as they keep the sauce a little more under control. Make sure there’s an extra bowl on the table for all those bones (which are a nuisance, true… but the meat is so good that it’s hard to care). Also make sure there are paper or cloth towels available—wet and dry—because you will get sticky from these things, no matter how you tidily you try to eat them. Just try to consider it as all part of that genuine rustic experience.

Serve with a green salad on the side, if you like. To drink with this, more of the cider you cooked in/with would be a logical choice… though light, pale bitter beers would also work well, to cut in on the richness of the dish.

Enjoy!

Meat, poultry, fast food