Rúasthë (Arlene “Lionhead” Festival Pastries)

- Background

- Ingredients and Directions

Legend has it that the foundation-stones of the keep that would become the heart of Kynall Castle (not to mention of the city of Prydon and the realm of Arlen) were set in place sometime during the tenday after the first of Spring, 1489 p.a.d. While the actual year-dating has been the matter of bar-room fights among Arlene historians for a good while now, the tenday immediately following Spring the First has for the last six or seven centuries been set aside for celebrations in the White Lion’s memory.

These always start out on a slightly somber note, with formal dawn solemnities at Orsmernin grove outside of Prydon. There at the ancient burial-place of Arlen’s royalty, the current Ruler, the Four Hundred, and as many of the citizenry as desire to join them, all come together in commemoration of the first battle of Bluepeak, of Héalhra Whitemane’s sacrifice there, and his subsequent assumption of demigodhead as the Lion. But after that the proceedings descend into a straightforward celebration of modern Arlen’s survival of the rigors of the past winter, and the first of the new early-season crops going in.

The ten days of the festival are a preferred period for weddings, birth-celebrations, and general feasting and merrymaking up and down the realm. In Prydon, the ruler of Arlen is expected to attend as many as possible of these seasonal get-togethers as the Lion’s representative, and (most particularly) to preside over the noisy public festivities of the Tenth Day among their people “with feasting and carousal / till moonset and beyond.” The old Arlene saying about being “as hung over as an eleventh-morning Sovereign”* (along with numerous raunchier variants, evoking other sorts of festival-associated overindulgence) is directly traceable to this expectation.

While a number of traditional Arlene dishes—mostly featuring fish and pork—are loosely associated with the Lion’s Days, one connection isn’t at all loose. Special festival pastries fried in lard, or (in regions where pork isn’t much raised) in local vegetable oils such as gourdnut, pumpkinseed or sunflower, are traditionally made in great quantities for the Lion’s Day holidays. Though some holidaymakers prefer homemade ones, for these ten days the pastries are available as street food pretty much everywhere—not to mention in every city bakery in Arlen. But regardless of the pastries’ source, whether in town or country a lot of Arlene people feel that the Lion’s Days aren’t properly begun, and can’t be allowed to pass, without having at least one or two of them …and preferably a whole lot more.

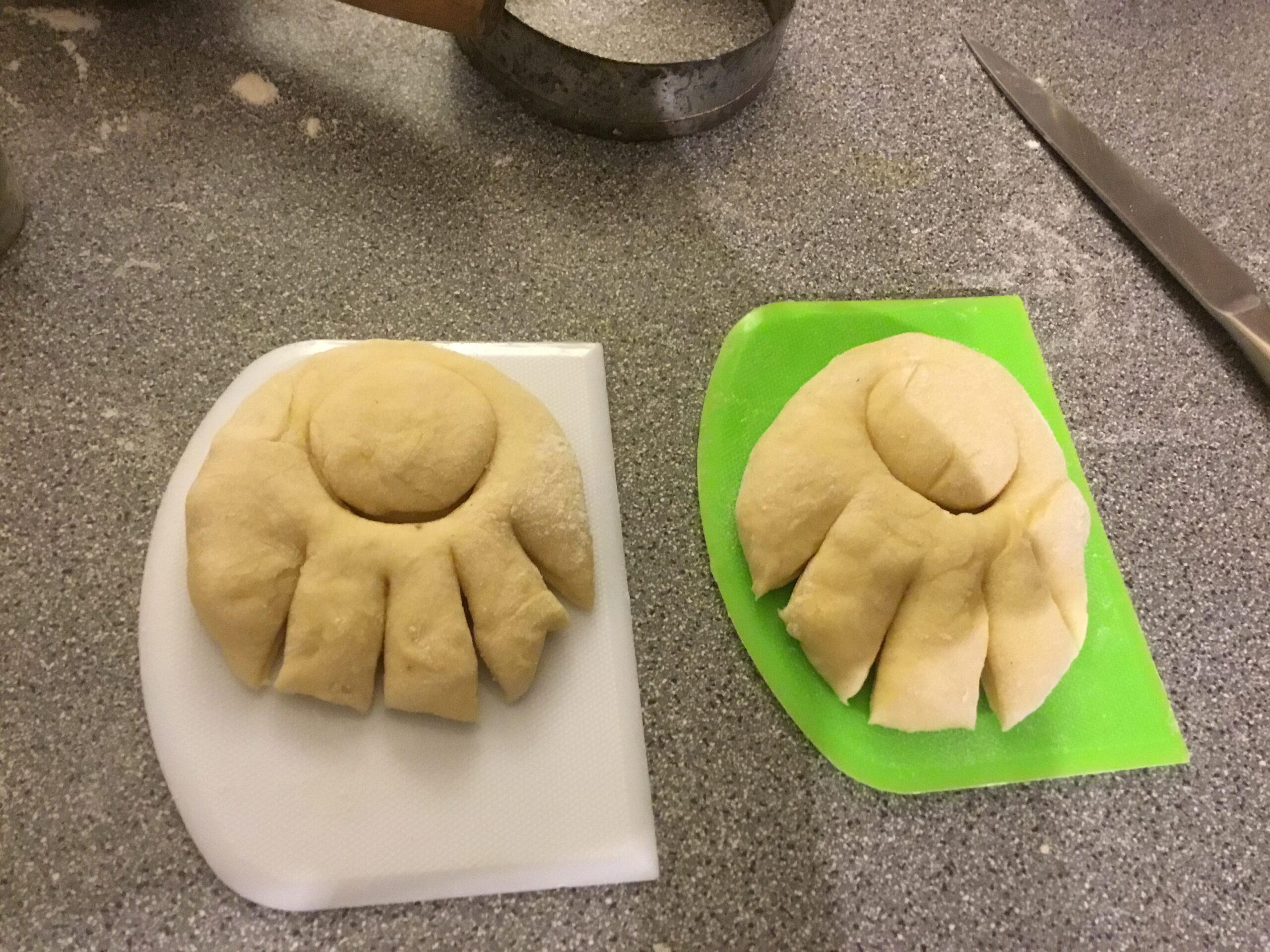

These pastries are based on a yeast-raised dough enriched with eggs and butter. After its second rise the dough is portioned out and flattened (or with firmer versions of this dough, rolled out and cut into rounds). Into the center of each of these is partially-cut the shape of a second, smaller round, so that (supposedly) they look like a male lion’s face and mane seen head on: hence their name, Arl. rúasthë or “lion’s heads”. While having their third, very brief “resting rise”, they may be scored or cut with a knife to reinforce this impression.

The pastries are then fried. Once they’re out of the lard or oil and have been drained, they’re flavored in a number of different ways, either sweet or savory (or sometimes both) depending on the purchaser’s preference. They may be brushed with honey (spiced, or smoked). Or else the honey may be merely a first step before the rúasthë are strewn with sea salt mixed with spices: cracked black or green berry-pepper, fine-ground allspice or dried whitefruit, and caraway (either dry-toasted or as honey-coated confits) are all popular toppings. In north-coastal Arlen, where sweetrush-derived crystalline sugar is more readily available, rúasthë are often rolled in it while still warm (as in our version), or drizzled with spirit-thinned treacle.

…As might be expected, Arlene people have differing (and sometimes strongly regional) preferences for how rúasthë should be made and eaten. Some bakers sell versions with a deep indentation where the face would go—filling that spot with a thick solid custard, cream or fruit compote, then adding a cut-out (and separately-fried) “face” on top. These pastries are called mirnrúasthë, “hidden (in the) lion”. Some claim that this name refers to a seasonal children’s game called “Hide the Lion”, which involves passing pastries from hand to hand around a circle while singing a very old rhyme about Héalhra’s fight with the Goddess’s Shadow. The one holding the pastry when the song comes to the end of a verse gets to “hide the lion” in the most straightforward manner: by eating it.

It takes little examination of the regional variations of the Lion’s-head pastry to grasp one constant: the further one gets from Prydon, the more conservative rúasthë treatments become. In the “debatable” shared land on the east side of Arlid—where to work out whether you’re in Darthen or Arlen may require either a sextant or a magic-worker—and in the “High South” near the Highpeaks or the “far north” close to the North Arlene border, people are likely to be scandalized if you try to offer them a pastry that looks anything but flat and palely-fried, and with a very conservatively cut-out head. In more central parts of Arlen, though, meaning Prydon city and the “midlands” regions, mad invention in terms of flavor, shape and treatment—what we would consider serious envelope-pushing—is rife.

As with cracknels, around the first of Spring some Prydon-based bakeries become hilariously competitive with one another—unquestionably vying for attention (and a possible Royal warrant) by creating versions of rúasthë involving unheard-of combinations of flavor and texture, especially as regards fillings. In other parts of the country, these efforts are written off as aberrations…“city folks’ madness” or unwarranted food-faddism. City people, on the other hand, see this exercise of unbridled creativity as part of their civic birthright, and reward its best-known practitioners with bumper business every year.

A lot of excitement starts to surround such establishments’ shop-hatches around the eighty-fifth of Winter each year, and the new Spring creations are paraded in the streets, heralded by drums and trumpets (and a Spring Morning discount that lasts no longer than it takes for the morning’s first-plucked bellflowers to wilt). Yet a thoughtful viewer of Prydon’s food scene cannot help but notice that the single bakery “up the Bluff” (as many Prydonai call the Castle Height) that does boast a Throne warrant is one that every spring, year in, year out, produces only the very simplest form of the pastry: fried in lard and markedly browner than those produced by more popular bakeries, perfectly round, with a featureless round-cut face—no filling, only the most minimal snipping at the edges to emphasize the mane, and only a brushing of smoked honey on top. There are city people who’ll buy their pastries nowhere else, calling these “the King’s lions”.

And if any of them have ever caught sight of a short, fair-haired, dark-cloaked form sneaking out that bakery’s back door in the dark before dawn on the First, they’re likely enough to keep the news to themselves. “He was a good while gone,” such folk might say if you caught them at a wineshop somewhere on the afternoon of the Eleventh. “Let’s not frighten Himself off the nest just yet.”

* “Hlemnëvh tei’ ast-Raïd Omorrúnedejte”. The morning of the Eleventh of Spring is widely considered to be an unofficial holiday in its own right (rather the same way that the day after Hogmanay is held in our Earth’s Scotland)… the reasoning being “If the King doesn’t have to go to work today, why should we?” It is also a day on which it’s assumed that almost all the bakeries will be closed.

Ingredients:

- • 500g strong white bread flour

- • 30-60g caster sugar / granulated sugar (superfine if you can get it)

- • 15g fresh yeast, crumbled, or a package of “instant” dry yeast. If your yeast isn’t new and fresh, you may want to make sure it’s still viable by proofing a small amount of it in lukewarm water & sugar. (This can be added to the recipe as long as the amount of water is small—10 ml or so—and you subtract that amount of water from what you’ll be adding in total.)

- • 4 eggs at room temperature

- • zest of half a lemon, finely chopped (or 1 tablespoon puréed lemon zest if you can get it)

- • 2 tsp fine sea salt

- • 125g softened unsalted butter

- • 100-140ml water

- • 1-2 quarts/liters sunflower oil for deep-frying (or a similar amount of melted lard, if you can source it)

- • more caster sugar, for tossing

Ingredient notes:

You’ll see that two ingredients above show more than one amount or quantity. These, depending on which you use—the smaller or the larger—will produce slightly different results in the pastries.

Using the smaller amount of sugar seems to work better for pastries that you intend to season with what we would think of as savory seasonings such as herbs or peppers.

The smaller amount of water produces a slightly more solid and “cakey” pastry, along the lines of a standard ring-shaped/nonfilled doughnut. The larger amount of water produces a softer dough and a lighter, more spongy fried pastry, more like what you would expect in a jelly doughnut.

Directions:

Put your chosen amount of water (either 100ml for cakier pastries or 140 ml for spongier ones) , along with all the dough ingredients apart from the butter, into the bowl of a mixer with a beater paddle. Mix on a medium speed for at least 8 minutes. (The dough may or may not form a ball at this point, depending on how much water you’ve added. The lower-water dough will almost certainly gather up this way. Dough with the larger amount of water will more likely go ribbony.)

Turn off the mixer and let the dough rest for at least 1-2 minutes.

After this resting period, restart the mixer at medium speed and slowly add the butter to the dough—one or two tablespoons at a time (around 25g each time, if you’re concerned about weighing it). With each new addition of butter, beat until the butter is well incorporated incorporated before adding the next.

Once all the butter has been added, mix on high speed for 5 minutes until the dough is glossy, smooth and very elastic. When you stop the beating and pull the beater up, the dough should follow it up and cling to it fairly hard, so that it will probably need to be scraped off with a knife or dough scraper.

Cover the bowl with cling film or a clean tea towel and leave to prove until it has doubled in size.

Use a spoon to stir the dough back down. Then re-cover the bowl and put it in the refrigerator (or other similarly cold place) to rise for at least 12 hours. Make sure the bowl is no more than half full at the start of the rising time, as (regardless of the cold) this rise can become surprisingly enthusiastic. (As below…)

The next day, take the dough out of the fridge and cut it into 50g pieces (you should get about 20). This process is best managed by scraping the whole business out of the bowl onto a liberally-floured work surface and rolling it into rope, then chopping it up into equal-ish portions with a sharp knife. (You might try simply pulling pieces off the main mass of the dough by hand. But with the softer/stickier type of dough, this is likely to leave you repeatedly sticking to everything involved in the process, and very frustrated long before you’re finished.)

Once you’ve finished with your portioning, roll each of the pieces out onto the counter into a tight ball and place them on a well-floured baking tray, leaving enough space between them so that they’ll avoid “kissing” when they rise.

Cover with cling film / plastic wrap, or with a dishtowel with a tight weave (linen is good if you’ve got one) and leave in a warmish place to rise until doubled.

When they’re almost ready, fill a heavy-based saucepan or heavy-bottomed pot with enough of your preferred oil to allow the fried cakes to submerge and be fully covered. (We used a wok for this, and filled it about 2 inches deep.) Heat the oil to 180°C / 355°F.

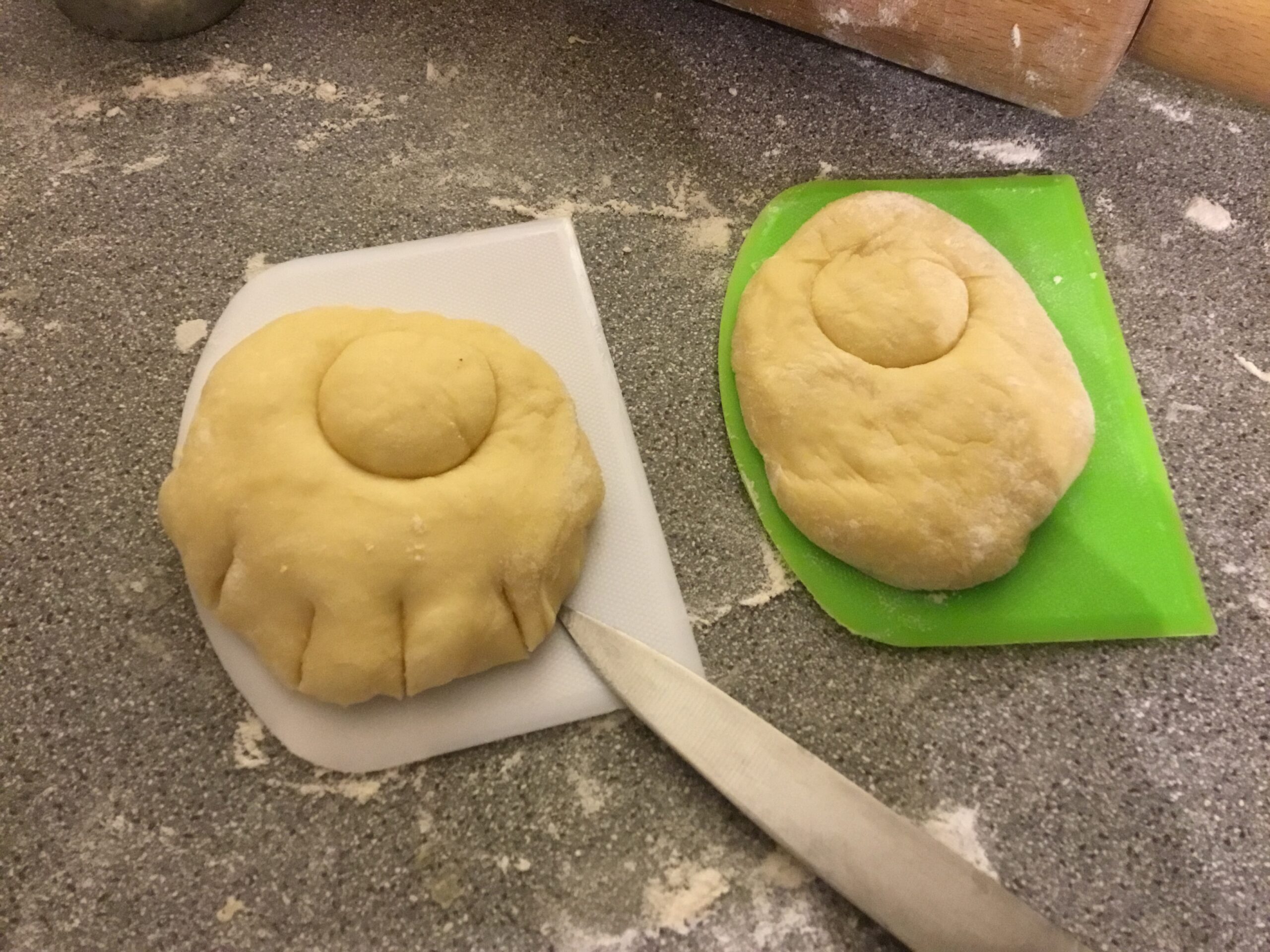

Now comes the tricky part: the lion-face cutting. Flour a work surface again and, one at a time, press or pat each risen ball of dough down into a round. With the smallest biscuit cutter you can find, or with a small sharp knife, cut a three-quarter circle into the top half of each round, being careful not to cut the circle completely free. (If you’re using a round cutter, a kind of slow rocking motion works best for this.)

Once you’ve finished this first bit of cutting, move each round onto a dough scraper or spatula and use a small sharp knife to cut a series of scores around (and through) the bottom edge of the round. When this process is finished, wiggle the pastry a little to be sure it’s loose and won’t get stuck to the scraper or spatula when you introduce it to the oil. You may find that you need to flour the pastry scrapers or spatulas (“spatulae?” Never mind…) to keep the pastries from sticking while they wait.

…It’s worth noting that this dough can be quite enthusiastic when in a warm kitchen, and pastries will routinely continue rising even after being cut and sitting around waiting on the dough scrapers.

Now you’re ready to start the serious business of frying the pastries. Having checked the oil to make sure its temperature’s stabilized, use the scraper(s)/spatula to carefully slide the first couple/few pastries into the hot oil. Do your best not to deflate them with too much rough handling when they go in.

The pastries may sink briefly, but quite shortly they’ll float to the top of the oil. Allow each pastry to fry for at least two minutes on one side (you’ll be setting up your next pair or trio of pastries while this is happening). Then nudge each one with a spatula or spoon to turn it over.

Give each another two minutes or so and then lift them out with a slotted spoon (or hook a fork through the “head space” that will open up in each) and place them briefly to drain on a plate with some paper towels. After that they should be removed briefly to a rack while you continue the frying process.

When they’ve cooled a little, you may want to test one of these first pastries for doneness. If yours have gone pretty brown but don’t seem done enough inside for your liking, allow your oil’s temperature to drop just a little (5°-10° or so) and try frying another test pastry for two and a half or three minutes on a side. Then see how that one suits you, and proceed accordingly.

…Continue this process until you’ve finished frying all the pastries. Keep checking your oil’s temperature all through the proceedings…as if it gets too high the pastries will burn on the outside and still be raw in the middle: too low, and the pastries will soak up too much oil and get heavy and greasy.

If you’re going to be doing the very northern-Arlene roll-the-rúasthe-in-sugar approach, this should happen while the pastries are still warm, so the sugar will stick properly. For other seasonings, the traditional approach would be to allow the pastries to cool completely, then brush them with honey and roll them in/sprinkle them with the seasonings of your choice. Right across the Kingdoms, the our-Earth-European-medieval fondness for combining sweet and savory elements in all kinds of dishes is a commonplace, so herbs and spices that we would normally think of as savory are often found being stuck to the pastries with honey. We found caraway and poppyseed to be nice this way. Sesame seed (especially toasted) would also work.

Enjoy!