Chicken and Honey Pastries

- Background

- Recipe

This perennial favorite of patrons of Patellan’s Steldene cookshop in Prydon (northside Third Wall Inner, open third hour past noon to second hour past midnight, no deposit on takeaway bowls after your fifth order) is routinely one of the first dishes people name when asked to describe Steldene cooking. All the cuisine’s most popular tropes are there at once. It’s sweet; it’s spicy (sometimes almost painfully so); it’s crispy; it reheats well; and it makes the usual inspired use of leftovers typical of a country that has over the centuries suffered far more than some other parts of the Kingdoms from food scarcity due to crop failures, natural disasters, and war.

The pastry has many regional names in Steldin, but the version best known and loved in the other three Realms usually goes by the name kaskef pa-hest, “[pastry-]wrapped spiced chicken”. As with so many Steldene dishes, its fame is founded not so much on its basic ingredients as on how and with what they’re seasoned. The most celebrated versions of kaskef pa-hest are made with native tesk-kaskef (“two-spice”) honey. This is a blended honey, its components produced by bees that have been pollinating the pair of spices most frequently used in the popular Steldene tesk-kaskef spice blend: iskef, or Piper cubeba medioregnis (the near-exact Steldene congener of our cubeb pepper), and birkef, the Middle Kingdoms’ unique Xenozanthoxylum microdraconis (to which our Earth’s closest congener is Zanthoxylum piperitum, the huājiāo, “prickly ash”, or Sichuan pepper).

X. microdraconis is significantly “hotter” than our so-called Sichuan peppercorn. The birkef berry (so-called: the spice proper is actually the outside casing of a seed pod) contains far higher levels of the capsaicin-analogue hydroxy-alpha-sanshool—nearly 9% in some subspecies—which is responsible for the Sichuan pepper’s renowned mouth-numbing qualities. The unique fragrance of the spice carries over strongly into honey made from its flowers… so that it took very little time for clever kitcheners to hit on the idea of infusing the honey with water- or syrup-based decoctions of the birkef berry, and then using it as a prominent ingredient, especially as an accent in savory dishes.*

On Steldene home ground, tesk-kaskef honey is relatively commonplace and easy to find in the markets even if it’s not made in one’s own locality. But unfortunately its fragrance is vulnerable to the kind of temperature changes and irregularities associated with long-distance transport; in short, it travels badly. As a result, people west of the Darst who’re trying to reproduce a favorite Steldene dish such as kaskef pa-hest are routinely thrown back on the (admittedly imperfect) strategy of finding a local honey with a suitable flavor—that is to say, one that doesn’t have too strong a floral or plant-character of its own—and infusing it with homemade decoctions of the paired spices.

Another thorny issue for connoisseurs of this dish is the nature of the chicken that stuffs the pastry. Traditionally this dish is made with leftover meat from the carcass of a whole roast chicken—dark meat, scraped-off back meat, and the chicken’s “oysters”—often toasted a little more in a frying pan over open flame or on the floor of a bake-oven, then finely chopped. The kinds and percentages of meat used in cookshop pastries will routinely vary depending on the preferences of their clientele (and their preferences as regards how much they feel like paying for the pastries). In shops looking to shave a little off their costs, the filling is likely to involve chicken that’s been boiled for soup, or (at the shadier end of the transaction) has been judged to be about to go off.

City cookshops with any kind of reputation, of course, would normally refuse to go down this road. If they err in execution, the error’s likely to go in the other direction—meaning the use of more upmarket parts of the chicken for the filling, such as breast meat (or at least mixing nontrivial amounts of it with the thigh and drumstick meat). It’s difficult to tell whether Patellans’, from which Herewiss brings back takeaway for Lorn in TOTF3: The Librarian, has taken this approach. Certainly there are establishments that, even though they might have access to a high-end clientele, would insist on doing the dish traditionally… that is, no meat fancier than drumsticks or thighs. Such foodmakers would describe the use of breast meat in chicken-and-honey pastries as naughtily nonauthentic—shamefully pandering to people too fond of their own high-end sensibilities to properly engage with the authentic dish, and a breach of the maker’s “understanding with the food”.

In any case: what you’re looking for here is the perfect starter for a Steldene meal—just spicy enough to get your mouth set for the excruciating-yet-delicious torment to come, just sweet enough to take your mind a little off the spice, just savory enough (and delectably greasy enough!) to take the edge off your first hunger and leave you ready for more. …And of course the pastry, when bitten, also ought to shower you with fragments of its crisp delicate buttery layers and leave you brushing (uselessly…) at your clothes for the rest of the evening, because otherwise the total experience would be lacking.

See the right-hand tab above for the recipe and method.

*There is actually a hard-to-find Steldene birkef-honey distillate—what we would think of as along the lines of an eau-de-vie—that’s much in demand among those concerned with the authenticity of their Steldene dining experience. It is variously described as “an acquired taste” and “not for the faint-hearted”, depending on the drinker’s tolerance for the buzzy, numbing quality of the sanshool. Here and there one finds a high-end cookshop using it in their pastry filling in an attempt to confer an additional air of authenticity on the final product. It would be difficult to express the scorn with which Steldenes would view such an endeavor—like putting actual steak in a Philly cheesesteak. The old Pherra-regional proverb about how “Kings may be drunk, but being drunk won’t make you a king…” is all too likely to wander through any ensuing conversation.

The recipe and method:

This dish falls broadly into three parts: the honey, the pastry, and the chicken. The honey requires the most lead time, so we’ll start with that.

“Steldene-style” honey

There are two approaches to a hot/spicy honey—buy some in, or make it yourself.

If you’re in the life’s-too-short, just-buy-it-in school of thought, there are a fair number of possible retailers. One well-known one in North America is Firebee. Another, in the UK, is Hot Fire Honey from Wales. Nose around a bit and you’ll soon find others.

If, however, you’re of a more DIY turn of mind, dealing with the spicy honey will take a couple of stages: acquire the kind and flavor of heat you want, and then find a honey that seems likely to go well with it.

There’s no need to get overly doctrinaire about the “local accuracy” of this ingredient if you don’t feel like it (i.e., no need to use Sichuan peppers if you’re not inclined). The only requirement is that the honey should have a perceptible kick of heat, and one that will go well with chicken. The Steldene approach, as stated above—when the true spice-honey can’t be acquired, or when there are other reasons for using a substitute—does contain their Sichuan “pepper”, as well as other spices, varying from establishment to establishment (and some, as you might expect, guarding their spice mixtures closely).

The method for making spiced honey, in any case, is pretty straightforward. Gather your spices—peppercorns, dried chiles (some North American chefs who’re into spiced honeys use Habaneros for this purpose), Sichuan pepper, long pepper, and whatever others suit your fancy. Crack them coarsely (in the case of the hard ones); bruise or smash them (in the case of chiles and Sichuan peppers).

Heat at least half a US pint / 8 fluid ounces / 240ml of honey until just at the simmer. It’s all right if tiny bubbles form, but under no circumstances allow the honey to boil, as its flavor and texture will change.

When the honey is hot, add the spices and reduce the heat. Stir well and allow the mixture to simmer over very low heat for fifteen or twenty minutes. Then remove from the heat and allow to mostly cool. While the honey is stll fairly runny, pour it into a heatproof jar with a lid, and seal it.

Put this jar aside for at least a week to allow the flavor of the spices and/or chiles to migrate into the honey. When ready to use, heat the jar very gently in a microwave or a bowl of hot water until the honey is fairly runny again; then strain it into another jar or the container of your choice and put it aside until you want it for the cooking process.

The rough-puff pastry

Ingredients:

250g plain flour (strong / high-protein flour—bread flour or similar—is best)

250g butter (cool but not cold: it should be relatively firm)

Pinch of salt

150ml cool-to-cold water

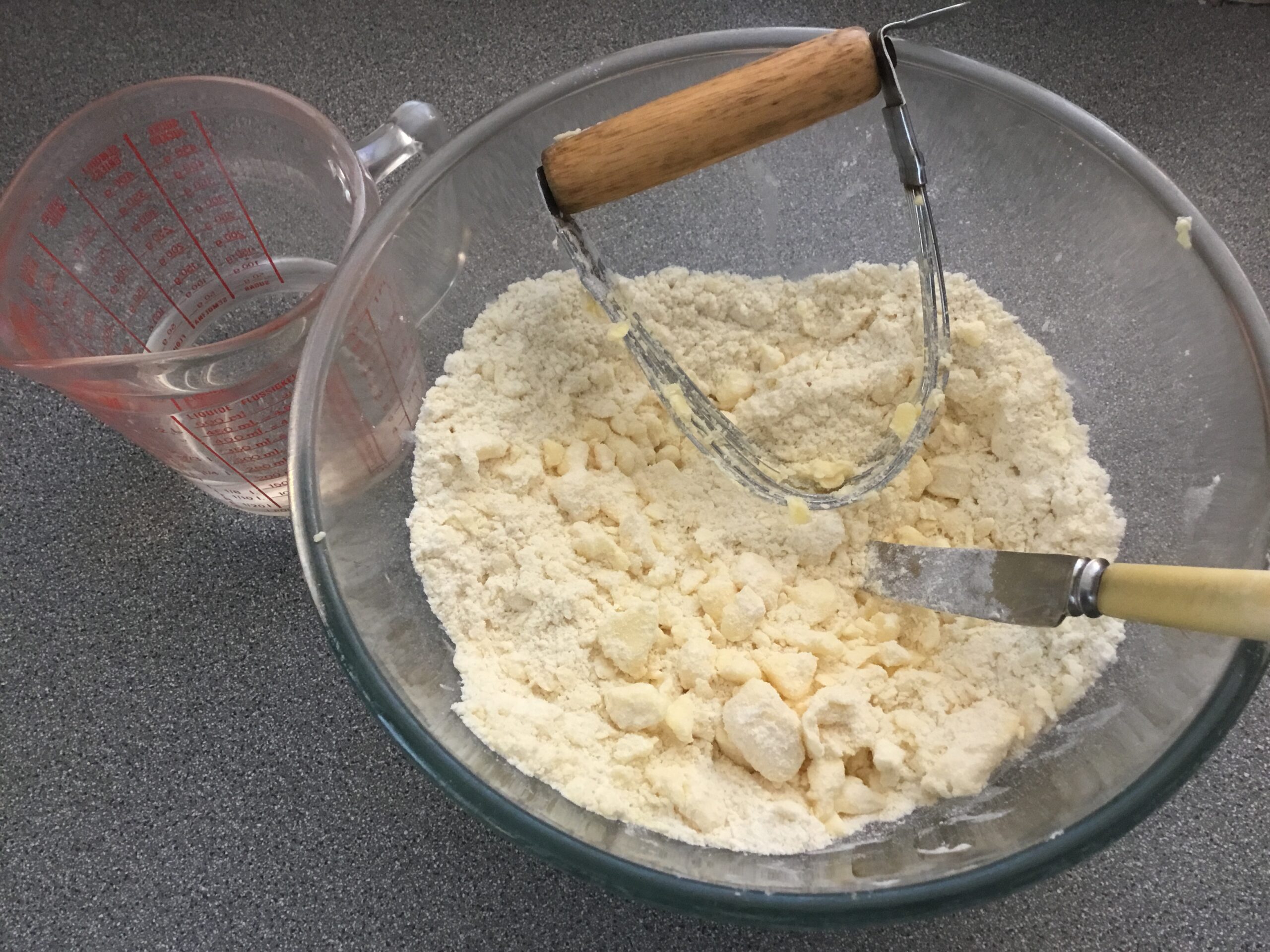

Mix the flour and the salt together. Cube the butter and toss it in the flour: then cut it in roughly. (You do not want the kind of fine-grained result one shoots for when cutting in butter for pie crust or similar. This pastry should show streaks when it’s rolled.)

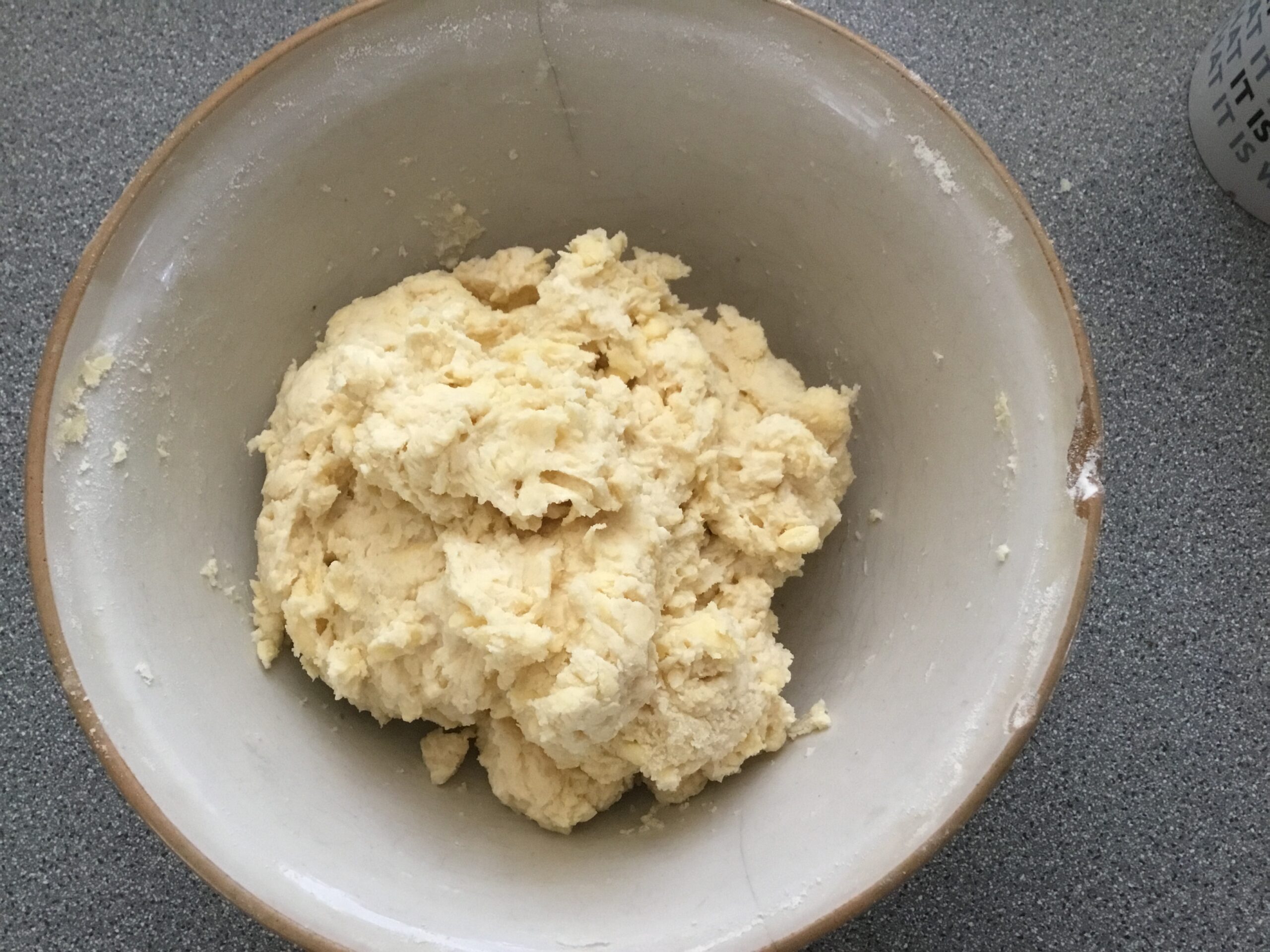

Add the water and mix it gently all together until everything gathers. If your flour’s being abnormally absorptive on the day you’re making this, add a very little more water if you have to in order to get everything to come together.

Cover the dough with a cloth, or plastic wrap if you prefer, and put it in the fridge to rest for about half an hour.

When this time has gone by: Lightly flour a work surface, turn the dough out onto it, and knead it very gently for just a few minutes until it smooths out. Shape it into a rough-ish rectangle.

Roll it gently in just one direction until it’s between two and three times as long as it’s wide.

Fold one third of it over the middle of the rolled-out part.

Fold the other third on top of the first one.

Turn it at a 90-degree angle and roll it just a bit more to smoosh the layers together.

Fold one-third of this business up over the middle again.

Fold the other third on top of it.

When that’s done, stick it in the fridge for another half hour or so.

Now you can go deal with the next set of ingredients…

The chicken

For the pastry stuffing, you need:

- The thigh, drumstick, wing (if you can get much of anything off the wings) and back meat from a large roast chicken (or two small ones)

- 1 finely chopped onion

- Seasonings: Salt, pepper, spices of your choice

- Butter or oil for sauteeing

Bone the chicken meat and chop it small (that is to say, into chunks no larger than 1/8 inch, if possible). If you have a Mouli-style food mill, you could use that to grind the meat up on a coarse setting. Or in a Cuisinart/Magimix, use the steel blade to pulse the meat until it’s very coarsely chopped. Don’t overdo this process: you don’t want a puree. The onion should be chopped to a roughly matching size.

As regards the chicken skin: Here as in Steldin, its inclusion is a judgment call for both the producer and the consumer. Some people like the flavor and fattiness of chicken skin in this mixture: some prefer to do without. If you opt in, you may like to toast the chicken skin a little under a grill (or in a frying pan) before chopping it up to go in with the rest of the chicken. Adding a little spicy seasoning to this process seems like an attractive idea; again, it’s your call.

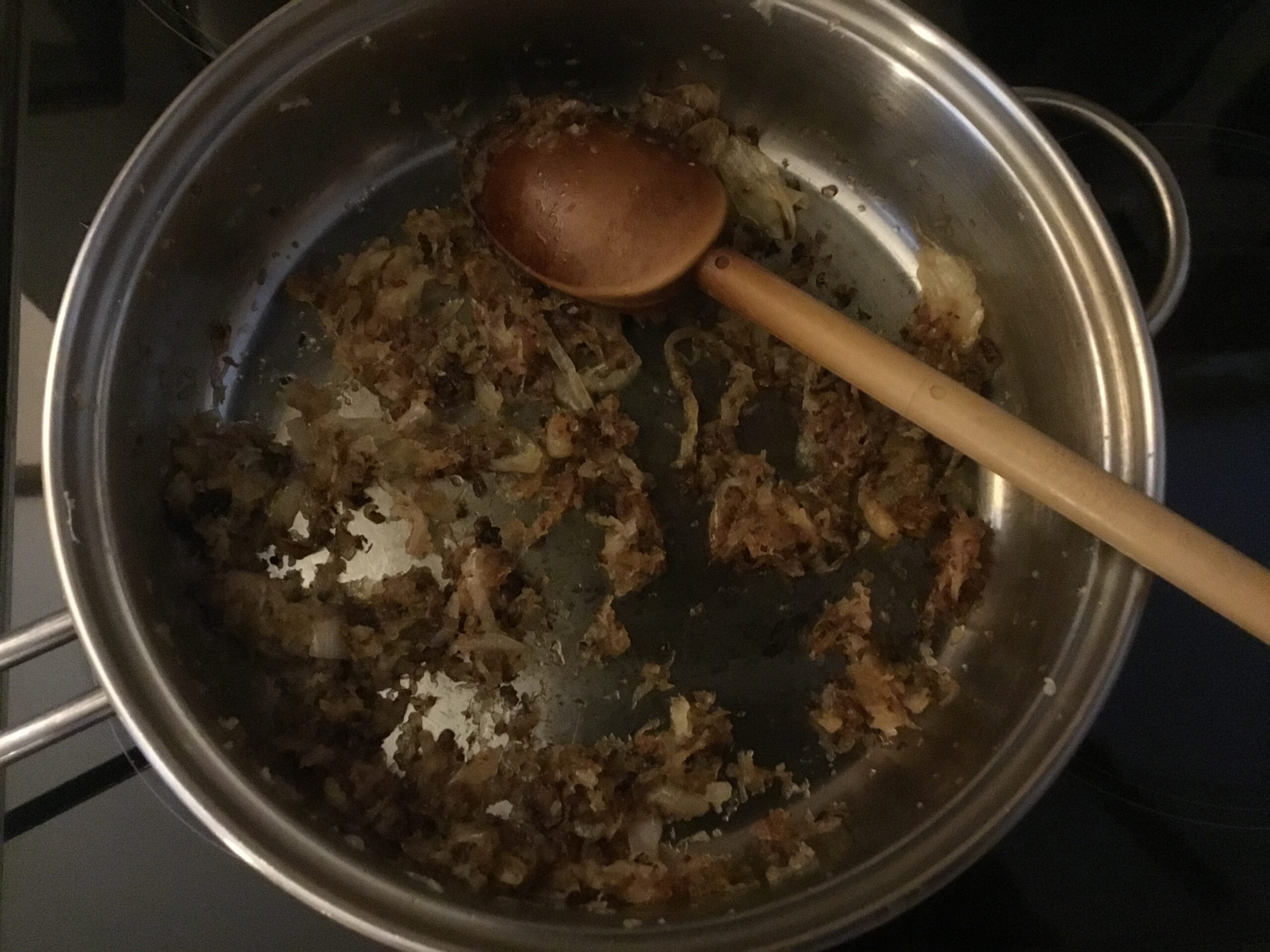

In a frying pan, with either butter or a little oil, saute the onions (and if you’re using it, the chopped chicken skin) until lightly browned.

Remove from the heat, and when cooled, put the sauteed mixture together with the other stuffing ingredients in a bowl and mix well together.

Season well with salt, pepper and whatever additional relatively hot spices you prefer. As whatever Steldene entrees follow these pastries in a regional meal are likely to be pretty aggressive in terms of their spicery, the goal with these starter pastries is normally to accentuate the savory rather than the merely mindlessly hot. To finish the stuffing mix, add several tablespoons of the spicy honey and stir well into the ingredients until combined.

Now it’s time to put everything together.

Assembly

Preheat the oven to 200C/400F.

Get the rough puff pastry out of the refrigerator, lightly dust your work surface with flour, and roll out the pastry to an oblong about 24 inches x 12 inches. Cut the pastry into squares, adjusting their size according to what size you want the finished pastries. Our photographed versions were made with both 4-inch squares (big enough to comfortably fill a muffin tin and fold over at the top) and 6-inch squares (for bigger pastries that we baked in small individual tart pans).

Line each of your pans with a square of the rolled-out pastry. Whatever its size, fill each pastry square about 2/3 full with the chicken and onion filling.

Over each one, squeeze at least a tablespoonful of the spiced honey—two, if the pastry is larger. (You can always add more if you like a sweeter pastry; though if you do, be warned—during the baking process honey will ooze out of the pastry and all over the place as things get hot.)

When you’re finished filling the pastries, fold the corners of the pastry square up and pinch them well together to seal.

Place spaced an inch or two apart on a nonstick baking sheet (or one lined with buttered or oiled baking parchment paper) and put in the preheated oven. Bake for 15-20 minutes or until golden brown. (Since the stuffing has already been cooked, your main attention here can safely be on the pastry. You don’t want it to scorch, but you do want to see it puff up nicely.)

When fully baked, remove from the oven and then (after cooling a little) remove from the baking sheet and cool briefly on a rack. Make sure you’ve put something under the rack, as these will drip leftover butter from their baking all over everything otherwise.

These are best eaten hot (and this is one of the reasons it can be really handy to send a Firebearer to bring them home from the cookshop…), but they’re also good just warm, or even at room temperature. If you’re not going to eat these within a few hours of their baking, freeze them to keep the crispness in the pastry. They reheat well from frozen. Ten minutes or so in a hot oven will do the trick.

Enjoy!